The arrival of a new superhero makes life turbulent for a team of journalists in “Our Hero,” Brandon Getz‘s stupendously subversive short story from our Winter 2019 issue.

{ X }

WHEN CAPTAIN MAPS CAME OUT OF NOWHERE to save that runaway bus full of blind nuns from careening into the river in the middle of town, we at the Daily Reporter had to admit: we were pretty relieved. With the advent of the 24-hour news cycle, the blogosphere, the decline of subscriptions and creeping corporate cutbacks, we had taken to pumping up even the smallest story. We had just finished apologizing for the O’Dougherty kidnapping (Local Girl Missing, Probably Murdered) after it was discovered she’d been visiting her grandmother for the weekend. That, on the heels of the school shooting debacle (they’d used cap guns in the eighth grade musical) and the clergy sex scandal (Father Michael, helping a woman in the confessional booth, had—allegedly—grazed her breast). We were anxious for real news. For one headline story we didn’t have to sensationalize. We needed a legitimate sensation.

Those of us who were there described, in those first articles and op-eds, the sound of the Captain’s approach before anything else. Rick in Sports wrote that it cracked over the voice of the announcer at the girls’ slow-pitch game “like God hitting a softball.” In the caption under the local weather map, Alex typed that it had sounded like “the mother of all thunderclaps.” But it was Hal in Lifestyles who, though we didn’t understand it at the time, perhaps said it best when he wrote that it was “a sound like a rip in the pants of the Universe.” We ribbed each other in the break room and near the fax machine over our descriptions, accused one another of being excessively literary or purple in our prose. Those of us who hadn’t seen the Captain appear heard so many stories about that moment that we soon spoke as though we had. We knew all the details: the sound, the ripple in the sky, the flash of green and blue leotard, the man hanging in thin air with the now-iconic cape—a map of the world—billowing behind him. The divisions between there and not-there, while at first tense and somewhat bitter, began to dissolve. We were united in our mission to report the truth. We pulled together in solidarity to deliver the news.

The first headlines were perhaps overly flattering. Caped Hero Saves Nuns, World. Super Man Rescues, Loves Town. Leotards: Pinnacle of Spring Fashion? Our editor-in-chief Roberta sent them to press with a flick of her manicured fingers. Roberta, whose face only cracked to sneer at a misplaced adjective or improperly cited source, now smiled when we brought her stories of the Captain. She stopped smelling of gin and limes after lunch hour. She even ventured to pinch the butt of Topher, the intern, and gave him what he later described as a “flirty wink.”

Our workdays grew longer. Because he had only appeared once, and only for a moment, our stories took on more hypothetical angles. Despite restrictions on overtime, we huddled together in our cubicles and speculated on his origins, his alter-ego, his motivations. Topher, being from a farm outside Topeka and possessing—according to some sources—a well-muscled physique, was immediately fingered as a suspect until it was confirmed he’d been at his desk playing minesweeper and writing terrible things about our newsroom on his blog. Someone suggested the Captain might be some kind of super-soldier from the Air Force base on the edge of town. Someone else said he could be a geography professor from the university whose experiment gave him superpowers. One of the obit writers wondered aloud if perhaps he’d been bitten by a radioactive map. Everyone was a suspect. We eyed strangers on the street and kept notes on suspicious persons in the grocery store or church. We rifled through our husbands’ dresser drawers and inspected the spaces under our brothers’ beds. We tapped the walls of boyfriends’ closets and garages, hoping for some hidden panel with a blue leotard and cape inside.

The newsroom buzzed. We held our breath, waiting for the next appearance of the Captain. We loosened our ties in what we thought was a cavalier and attractive way. We wore shorter skirts and started leaving our cardigans on the backs of our chairs. Roberta, who never wore anything but gray pantsuits, came to the office in red slacks and heels. When she sent article corrections back, she no longer signed her notes “EIC,” replacing it instead with a swirly cursive “Roberta” punctuated with a lipstick kiss.

Then Captain Maps saved city hall from that meteor. The air rippled; that same heavy thunder-snap “like God rolling a perfect strike,” as Rick wrote, cracked through downtown, and the Captain was flying above our little skyline, upper-cutting the big flaming rock back into space from whence it came. The crowd that had gathered cried out in joy. Children wept. The mayor, interviewed by our Lifestyles section, reported an impressive bulge in the front of the Captain’s green briefs.

This was the news we needed. Our stories were picked up by AP and Reuters, translated into a dozen languages. Photos from our very own photographer, Rashid, ran on the front pages of the Times and the Post. Our bylines were everywhere. We were booked on Fox, CNN, MSNBC, ESPN-3, The Weather Channel. On national TV, with our makeup professionally done and our designer suits bought on credit, we gave our expert eye-witness accounts of Captain Maps. We were the media’s front lines. The boots on the ground re: the world’s first living superhero. On those news sets, or in our own conference room chatting via satellite uplink, we conducted ourselves like professionals. We imagined ourselves the Edward Murrows and Connie Chungs of a dawning era. The Captain was the biggest news of our lifetimes, and we were the commentators, the shapers, the voice.

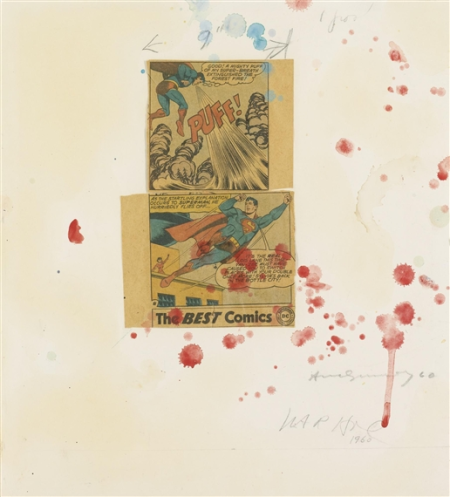

Subscriptions soared. Our website crashed from so many hits. We wrote about our hero from every angle, interviewed every witness, editorialized and hypothesized. When we ran out of things to write, we dug deeper. Caped Crusader – Hero? we taunted. We needed to know. We needed to be the ones to break the story. It wasn’t enough for the Captain to put our town—and our newspaper—on the map. Captain Maps was ours, right down to the name, which either Hal or Jeanine, our Business Editor, had coined the day of his first appearance, depending on who you asked. Roberta had sent in the copyright on behalf of the paper. We were talking to toy companies about licensing. Some of us had started working on screenplays. On the walls of the newsroom, we hung posters of that first front page to remind us of our greatness, our bylines next to an artist rendering of the Captain in all his cape-waving comic book glory. When we dressed for work, we wore subtle combinations of green and blue, his unofficial fan club.

Weeks passed. Even if it hadn’t been an election year, there were always wars and famines and water shortages and terrorist attacks. There was always news, but by then we weren’t interested in the misery of the world. Without any new appearances from the Captain, newsworthy heroics, we were fading from the national eye. We’d ridden the Captain’s cape into the limelight, and now he was shaking us off, back to our small-town beat. Jeanine, who’d written about the town’s much-needed tourism surge, reported a drop in the local economy. Captain kitsch—balloons, t-shirts, cheap plastic dolls—washed from the gutters into the river, unbought and forgotten. Alex, in a last-ditch effort, rigged a spotlight on the roof, painted over with a blobby North and South America, shining it into the night sky for days until Roberta told him to stop wasting electricity.

Soon there were reports of the Captain saving people in India, Morocco, Papua New Guinea. We felt betrayed. More than one of us burst into tears near the photocopier. He had abandoned us. Captain Maps had been our exclusive, our hometown hero. Now he was saving the world while we were drowning. Some of us started taking dark alleys on our walks home. We kept to the worst parts of town, our phones ready to record our salvation. Hal was mugged and lost his phone and thirty dollars, but still the Captain never came.

It’s hard to remember who had the idea first. Probably someone in obits. It was Hal, however, with a designer ski mask over his beautiful face, who stole the purse from that old lady. For days after, our front page read, Crime Surges – Hero Does Nothing. City Under Siege, Captain Shrugs. Super Do-Gooder Disappoints. By that time, the world had forgotten our little city. The Captain was on the front pages of the Times and the Post and the Tribune and a dozen small-town papers from Caracas to Constantinople, but he wasn’t on ours. Even in an era when news had become entertainment and truth in journalism was a quaint anachronism, our papers didn’t sell. Letters to the editor filled our inbox, calling us exploiters, charlatans, villains. We weren’t villains. We were only trying to sell print news in an era when everything had not only gone digital, everything was editorial—iNews, consumed to reinforce a worldview the reader already had. News didn’t sell newspapers. Not anymore.

After that, we lost heart. Even the most interesting news story was couched in the blandest terms. We were the opposite of what we had been. After the Captain, nothing was sensational. Even the explosion at the chemical factory, a legitimate disaster, elicited the tame headline Poof at Chem Plant, buried on page A3.

We were back in the red. Subscriptions flatlined, advertisers bottomed out. Roberta, in the grayest suit she owned, sucked on a cigarette in the middle of the newsroom and announced, bleary-eyed, that there would be cutbacks. Ed the Night Editor was forced to retire—we couldn’t afford to keep the lights on after 5 p.m. Topher, though he wasn’t paid, drank too much water from the cooler and had to pack up all the action figures he kept in his cubicle. On his blog, he called us all “fagsicles” and claimed he’d been “shit-canned.” He posted a picture of himself peeing in the photocopier. Roberta, bottle of gin half empty on her desk, said we didn’t have the money to sue. Or to fix the machine.

There were those of us, however, who were not deterred. Those of us who were reporters in our bones. We knew Captain Maps was our salvation. He was the only news that mattered. We stayed late, long after the lights had been shut off, our faces lit by the glow of our laptops. Our wives and boyfriends called, phones buzzing as we let them go to voicemail. Days went by without us seeing our kids. Stains blossomed on our skirts and khakis. Our clothes stank of sweat and cigarettes, our hair frizzed or flattened with grease. Most of us forgot to eat, subsisting on stale coffee and saltines from the break room. Together, independently, we started digging into the dark web, the underbelly of the information superhighway. We traced the Captain’s movements, his sudden appearances and disappearances, triangulating locations based on where headlines featuring the Captain appeared. We found composite images of his face and body type and paid hackers, from our own savings accounts, to run illegal facial recognition scans. Between writing puff pieces for our website, clickbait like 31 Reasons Captain Maps Sucks (You Won’t Believe Number 5!) to generate ad revenue, we began feeding anonymous threats into every corner of the Internet—bomb scares, terrorist plots—and waiting to see if the Captain would show. Nothing worked. The posters of that first front page were still on the walls, but the eyes of the Captain’s likeness were all X’ed out. Darts and pencils protruded from the globe on his chest.

To hide the stains, we started wearing black, like it was our own funeral. Black jackets, black leggings, black boots. We wore it almost as a uniform, with the odd purple pinstripe or lime green socks when someone felt especially daring. Roberta took to brooding in her office long into the night, even after most of us had fallen asleep beneath our desks. Her pantsuits darkened from gray to charcoal, until finally she settled on a black leather number with high, padded shoulders. When she shaved her head, some of us found it sexy. But the monocle was a little much.

We stopped calling each other by name. Instead, we’d say Weather Man, Ms. Gossip, The Obituarist. We called Hal “The Mask” even after he asked us not to. None of us were who we used to be; or we were, in a baser form.

Juiced up on cheap coffee, we huddled together in the darkness of the office, plotting. We hadn’t put a print edition on newsstands in weeks. We’d stopped bothering with local stories, with wars, with politics, with the weather. Captain Maps was the only news. And anyway, we didn’t have the money to pay our printing costs. The rent was overdue on the offices. Our corporate parent company had cut all ties. Even our online advertisers were abandoning ship. We’d be evicted by the end of the month.

We needed a real story. We needed an exclusive. Our eyes ringed purple with exhaustion and eyeliner, we edged closer, pens at the ready, toward our final story: the unmasking of Captain Maps.

It didn’t have to come to this. If the Captain had remembered us, if he had brought us with him in his journey to fame, if he had said thank you, he might have stopped us before we ever started. We had loved him, and he left us in the dust, small people in a small, flyover town.

Reports had been coming in for a while about strange occurrences near the site of the chemical plant disaster. Frogs bursting into flame, birds disappearing in clouds of smoke. It was Roberta’s idea to go. Our fearless editor-in-chief led us single file to a delivery truck in the basement garage, monocle gleaming, leather pantsuit squeaking as she marched. We packed in, elbow to elbow, a mass of black fabric and body stink. For most of us, it was our first time out of the newsroom in weeks.

Whatever we were expecting at the chemical plant, no one predicted that the ooze would just be there, waiting. Getting through the chain-link fence had been easy enough, with Roberta’s bolt cutters. The building itself was half demolished. Charred bricks littered the grounds. We crawled through a hole pasted over with yellow police tape and made our way inside.

Roberta tried it first. The ooze glowed, as one of us would note, “like the pink heart of God” in the darkness of the factory. Roberta, muttering something about the Captain and the bitter taste of revenge, plucked the vial from the flame-scorched cabinet, and downed it like a shot of top-shelf gin. Our fists squeaked in their leather gloves as we tensed and held our breaths. We almost didn’t notice when the alarm began to blare. Roberta shook violently, red warning lights reflecting on her shaved scalp. Her monocle clattered to the floor. Then she stopped and opened her eyes, the whites of them humming bright red. She winked and a nearby chair burst into flames, and The Mask said maybe we had another breaking news headline after all. Roberta passed more vials around, and we all took a guzzle. What did we have to lose?

A kind of purple fog swirled around Hal, and Alex from Sports swelled up with muscle like a tumor with fists. Blue lightning crackled around Jeanine’s fingertips. The rest of us, too, changed—black wings sprouted, skin turned green, ice swirled from fists frosted over. It hurt like hell, and some of us no longer looked human. It didn’t matter. We hadn’t felt human for a long time.

Every superhero has a weakness, but we weren’t looking for Captain Maps’ kryptonite. We only wanted his attention, to get the exclusive we were owed. Without knowing what else to do, we went back to the source. The first thing the Captain had deemed worthy of his attention in this world. The first time our hero unzipped space-time and swooped in to save the day.

By the time the SWAT team surrounded the office building that housed our dark and cluttered newsroom, the cops staying at least fifty yards away per Roberta’s orders, the plan was in full swing. We would bring the Captain back. We would get our story. Helicopters buzzed over the roof. Spotlights splashed across the windows. The newsroom had been emptied of cubicles, and Roberta paced, shining in her leather pantsuit. The rest of us stood at the edges of the room, away from the windows, our gloved hands ready with pens, pads, and tape recorders. Hal wore his signature ski mask. The rest of us left our faces uncovered. It didn’t matter—we were unrecognizable, even to ourselves. The hostages were in the center of the room, weeping. They wore black too, for different reasons. If we wanted the Captain’s attention, we needed something we knew he cared about. Even with Rashid’s X-ray vision, it wasn’t easy to kidnap a whole busload of blind nuns. But Roberta had a plan, and in the end, we found them all, even the one hiding in the confessional booth.

Now we had a headline: Daily Reporter Issues Challenge to Superhero—Blind Nuns Held Hostage. There was no story yet. We were writing it as we went. So all we printed was the headline, on the last of the pulp, and delivered it in the dead of night to the town’s newsstands. It didn’t take long for someone to realize it wasn’t fake news this time. The nuns were gone. When the police chief finally called, Roberta clenched the phone in a leather-clad fist and told him we only had one demand: We wanted Captain Maps.

As the nuns wept, we rocked nervously under the X’ed-out eyes of our posters of the Captain. We fidgeted with our new powers. Puffs of smoke and flame bloomed and disappeared like defective fireworks. Ice shards fell and melted into puddles. Some of us phased in and out of this plane of reality. Trying to lock down his own exclusive and betraying all of us writers and editors, Rashid set up a hidden webcam and soon we were streaming live, waiting for Captain Maps to show. Within minutes, the video went viral. Later it would be used in trials and Senate hearings, but just then it was our deliverance: the pants of the Universe ripped, the spotlight-swept windows of the newsroom shattered in wild sprays of glass, and there among us, thick hands knotted into fists, brows furrowed beneath a simple blue mask, was our hero.

Even with superpowers, most of us were not brave. We didn’t get into the news business to be heroes. We were writers, people who tapped keyboards and hid behind our words. Better journalists than us may brave battlegrounds and natural disasters, but we were a small town news team, more comfortable writing about spelling bees than speeding bullets. There, face to face with the square chin and comic-book muscles of Captain Maps, we were thankful that our skirts and pants were black so no one could see the stains. But we smelled it. It smelled just like the Xerox machine.

In a blue-green flash that rustled loose paper and tousled our hair, Captain Maps was in front of Roberta, globe-adorned chest puffed out and both fists triumphantly on his well-shaped hips.

“Breaking news, ma’am,” the Captain declared. “Your reign of terror is about to be out of print.”

On Rashid’s secret webcam, all of this was streaming around the world. We didn’t know it, but we were famous again. For that moment, we were news.

Ms. Gossip fired the first question. The Mask began shouting another even before she finished, the Obituarist barking something over that. Soon it was a barrage, a hail of inquisition. We had to know. This was our exclusive, finally our one-on-one. We circled like jackals, forgetting about the nuns and the police and how the Captain, powerful beyond our comprehension, had once punched a meteor back into outer space. Our gloves clenched around pens and tape recorders, we asked everything we could think of, hoping for some answer, some kernel of truth. Question after question until we got to the important ones: What did we do? Why have you forsaken us? Why are we not worthy of being saved?

Maybe it was the heightened moment, or the frustration we felt as Captain Maps, stepping back as if struck by boulders, failed to answer a single question. Around the room, eyes and hands began to glow and smoke and catch flame. Rashid snapped photos with bright flash, and the spotlights kept up their rhythmic sweep, a schizophrenic strobe effect illuminating the darkened newsroom, the Captain’s eyes white and dumbstruck behind his mask.

Later, as we attempted to write our articles and memoirs from our specially constructed underground cells, we would argue over who landed the first blow. Some of us agreed with Scott, the Muscle, that it was his giant fist delivering a left hook to the Captain’s perfect jawline that started the melee. Others remembered Jeanine, a.k.a. Newsflash, blasting blue lightning through the newsroom like a bolt from the gods. But the most loyal of us knew the truth: Roberta started the fight, her eyes glowing hellish red and her whole shaved head catching flame. After his cape and briefs caught fire, it was over for the Captain. Sure, Scott’s punch made him dizzy, Jeanine’s lightning made his hair stand on end, and Hal’s swirls of smog blinded him to the rest of our attacks. The rest of us, too, all contributed in our own way: sonic screams, ghostly teleport attacks, trembling daggers of ice and iron and bone. But it was our fearless editor-in-chief who knew what kind of story the reading public would clamor for. What headline would sell a newspaper. Strutting forward in her bright red pantsuit, blowing her deadly kiss as the rest of us shouted queries like cub reporters, Roberta started the fire that would consume the world.

In the end, of course, the Daily Reporter didn’t run the story. Death of Captain Maps ran on every front page across the globe, but not ours. By then, there was no Daily Reporter. Only us, in our cells, carving our stories into the walls. In the articles that appeared the next day, written by reporters who were better than we ever were (or at least less prone to hyperbole, less loose with the facts), the blind nuns—who’d all escaped unharmed—offered their eye-witness accounts. The smell of smoke and sulfur. The shriek of our voices. The final boom like “the seven trumpets of Revelations,” according to the Mother Superior.

When the police finally stormed the building, after the nuns had shuffled down the fire exit and Roberta had launched her kiss of death, the beginning of the end, they found us hunched over laptops, scribbling in our notepads, rewinding our tape recorders. At the center of the room, visible in the blue glow of our screens: a spattered mask, and a cape with a sigil of a map of the world, ragged and black with flame. But by then Captain Maps was just an obituary. We had copy to deliver, news to report. As we tapped furiously at our keyboards, Roberta stood over us, snapping her fingers, small fires on her fingertips igniting and snuffing out.

{ X }

BRANDON GETZ earned an MFA in fiction writing from Eastern Washington University. His work has appeared in F(r)iction, Versal, Burrow Press Review, and elsewhere. His first novel, Lars Breaxface: Werewolf in Space, is slated for release October 2019 from Spaceboy Books. He lives in Pittsburgh, PA. Read more at www.brandongetz.com.

BRANDON GETZ earned an MFA in fiction writing from Eastern Washington University. His work has appeared in F(r)iction, Versal, Burrow Press Review, and elsewhere. His first novel, Lars Breaxface: Werewolf in Space, is slated for release October 2019 from Spaceboy Books. He lives in Pittsburgh, PA. Read more at www.brandongetz.com.